On the Corruption

Perceptions Index, Transparency International gave the DPRK a score of

8/100, which means it ranks with Afghanistan and Somalia as one of the three

most corrupt nations in the world. Will North Korea ever be able to uproot the

systemic networks of corruption that has taken hold since the famine of the mid-1990s?

Would doing so necessarily promote equality? It might be fairly contended that

there is a functional (even egalitarian) element to the way that bribery in North Korea increases upward mobility for those with poor songbun and greases the wheels

between private sector enterprises and the government agencies that regulate

them. In fact, without the prospect of receiving bribes, public officials would

have very little incentive to do their jobs. Nobody in their right mind will

argue that today’s bribery-laden North Korea isn’t better off than it was 15 years ago.

However, it’s hard to ignore the very real presence of a different type of

corruption, that which is not only counterproductive to economic growth and

political management, but also increases stratification and embitters the

populace.

Image: Jonathan Corrado |

In the first segment of this series, I

presented a wide angle view of patterns of corruption in China’s People’s

Liberation Army (PLA) and the Korean People’s Army (KPA). I explored how differences

embedded in the political and financial structure account for variations in

corruption. In this second segment, I’ll try to shine a light on some of the

detrimental net effects of corruption in North Korea in order to assess whether a

crackdown can even be considered a worthwhile or necessary endeavor. To

understand the essential role that bribery, graft, and kickbacks play in

contemporary North Korea, I’ll also go back in time to discern how they became the

standard operating procedure.

What Happens When an Entire Military Goes

“Under the Table?”

In May of 2014, a Pyongyang high-rise

containing the families of senior Party cadres and military officers collapsed.

Although the exact figure is unknown, it is believed that dozens perished. The

building’s construction was accelerated as part of a speed-housing-project ahead of the 100th anniversary of Kim Il Sung’s birth. It was carried out by the 7th Bureau of the

Ministry of People’s Armed Forces. In response, central authorities conducted

an “intensive investigation,” which resulted in 7th Bureau officials passing

the buck all the way up to Jang Song Thaek – who allegedly stole concrete from

them – and was conveniently, by that time, already dead. Although any officer

who had a hand in this scheme will likely take their secrets with them to the

grave, this construction project, like most undertaken by the KPA, was most

likely a hot bed of embezzlement, graft, extortion, and bribery.

Kim Jong Eun consults with the members of the National Defense Committee on the construction of large scale housing in Pyongyang 2.15.2015. Image: Yonhap News Agency |

In an interview conducted with the Daily NK,

a North Korean with experience on construction projects said that, “general

managers command workers to bring in things like concrete all the time. When

workers say they can’t get the materials because they don’t have the money,

they respond by telling them to go and borrow supplies. It’s so hard when they

keep asking us to pay for things…We can’t all turn to stealing.” According to

other inside sources, collapses that stem from shoddy military workmanship like

the one above are quite common. In this context, it’s no wonder that the regime

showed signs that they‘re fretting about public perception. In an attempt to

nip any antipathy toward the regime itself in the bud, a rumor began

circulating that Officers from the 7th Bureau patently ignored Kim Jong Eun’s

explicit orders to focus on safety.

In addition to becoming a tremendous burden

for the rank and file, the corruption problem has also led to large-scale

military inefficiency. This

includes a very high desertion rate, officers needing to travel to the

jangmadang to purchase fuel out of pocket, and the incidence of mass suicides

among abused and starving soldiers. Lee Jin Woo, a 10-year veteran of the KPA, told

the Daily NK that torpedo boats ordered to mobilize during the first West

Sea battle in 1999 could not move because their fuel had been sold at the

market by the officers. In light of this, it isn’t hard to see how graft,

corruption, and insubordination pose a problem no matter how you look at them:

from the top down or the ground up.

According to a native Pyongyang citizen,

the already complicated process of buying a mobile phone has recently become

even more difficult because of corruption. Even if you manage to work your way

through the dizzying bureaucratic maze of certifications and approvals, you’re

still not guaranteed a phone. That’s because the government has recently had

trouble selling a device called a watt-hour meter. So they are requiring all

phone subscribers to purchase the useless $32 meters, which essentially amounts

to a “telecommunications tax.” Those who refuse to purchase the meters and

submit the receipt have had their service discontinued. Viewed individually,

these episodes seem like the quirky misfires of an incongruous polity. But

taken together, these scenarios underline the fact that unchecked corruption

inevitably causes dysfunction, waste, inefficiency, and ultimately, disaster.

Genesis of the “Under the Table” Ethos

Troops from KPA Unit 1313 Cheer on Kim Jong Eun during a respite from winter training exercises 12.5.2014 Image: Yonhap News Agency |

Kim Jong Il created an economic system that

parsed the market into three tiers. He rewarded his loyal inner circle in the

Chosun Workers’ Party with lucrative deals in mining, fisheries, and exporting

as well as access to elite banking systems. The KPA was given the second tier:

construction and heavy manufacturing. Ever since rations dried up during the

1990s famine, ordinary citizens have been relegated to eke out a living from

the leftovers in the third tier: a sector defined by an ever changing array of

strict rules and regulations designed to ensure money flows upstream to tiers

one and two.

But the cleavage between these sectors is causing economic

disruption and damaging the foreign currency management system, which is

important to domestic interactions because of the unstable value of the North

Korean Won (KPW). The regime is so hard up for liquid that they’re requiring

all households to

contribute 5kg of kidney beans for export as part of a “loyal foreign

currency” movement. Tier one or “royal court” banks can swoop in and undermine

the profitability of other banks at any time. This makes it harder for tiers

two and three to raise capital or grow their enterprise. The party also amped

up its call for steel this year, forcing factory managers to “grudgingly

dismantle presently unused or older machinery to fulfill the steel quotas.”

John

Cha, author of Exit Emperor Kim Jong Il, calls North Korea’s economy “a chopped up,

disconnected system that is not designed to facilitate economic flow and

circulation.” After massive inflation in 2002 and a devastating re-denomination

in 2009, the KPW now trades at ~8,300 won/USD.

The economic crisis in the 1990s gutted most

national agencies, forcing each department to raise funds independently. State

employees were, and continue to be, paid a pittance for their labor. This

necessitated the extensive and pervasive use of bribes and kickbacks to fill in

the cracks between state-sanctioned projects and private enterprise. Members of

the public and private worlds now exist as mutual hostages of one another,

unable to live with or without their counterparts.

The DPRK continued its Songun policy

throughout the famine, meaning that while rations dried up elsewhere, there

were still limited supplies available to soldiers up to the early 2000s. Film

footage smuggled out of North Korea by a defector in 2006 clearly shows the

military reappropriating rice aid shipments coming in from South Korea. Despite

swallowing up 50-70% of these aid shipments and receiving money from the

Worker’s Party, the sheer size of the KPA means that they nonetheless must

create much of their own revenue. They do this through the production and sale of

munitions, construction and infrastructure projects, operation of power plants,

and ownership of heavy manufacturing companies.

Despite helming some profitable

operations, the KPA’s food chain does not extend in any meaningful way down to

the lower ranks. The General Federation of Rear Services is tasked with

providing the nation’s 1.19 million soldiers with 800 grams of corn/rice per

day, but they often fail to give more than 500 grams (or about 500-600 kcal,

~25% of the nutritional intake required for an active adult male). Many

soldiers therefore need to take monthly trips back home to fatten up. Some have

been caught slipping across the border to China to steal from private homes,

creating tensions with Chinese leadership.

During the famine, families were eager to

send away their kids to the military to have one less mouth to feed. But these

days potential recruits have begun resorting to drinking a bowl of soy sauce so

that their liver appears bloated and they fail their conscription health test.

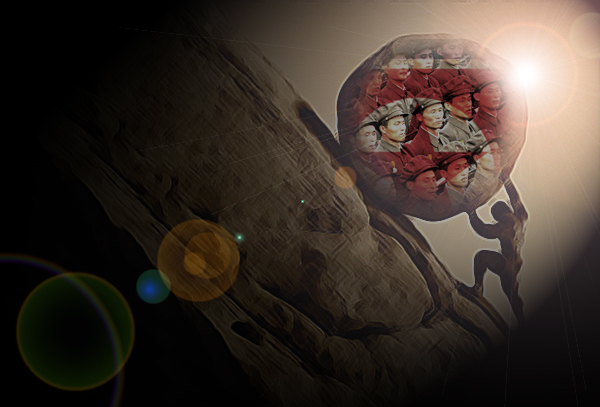

Once consigned, KPA soldiers are locked in a Sisyphus-like existence, living

hand to mouth while struggling to comply with impossible demands from superior

officers. Rations are in short supply, requiring soldiers to beg, borrow, and

steal vegetables, meat, soap, shovels, toothbrushes, wood, etc. In 2012,

soldiers from the 8th army corps were ordered

to procure 200 power saws, 200 shovels, and 100kg of nails. Because the KPA

is unable to issue funds for the purchase of said equipment, the soldiers are

urged to beg, borrow, and steal.

Despite receiving 25% of the nation’s

(albeit meager) GNP, not enough funds get through to feed or equip soldiers

properly. According

to an inside source, this is because “embezzlement and bribery are the

only methods of increasing the wealth of military officials and superior

officers.” So even when the Ministry of People’s Armed forces does issue

supplies, the pilfering is so severe that barely anything gets through to the

lower ranks. Instead, bookkeeping officers, deputy leaders, and sergeant majors

siphon off goods like food, fuel, and uniforms and bring them to sell at the

jangmadang. A defector from the 5th corps said that at least 10% (10-30

soldiers from each 120 person company) end up deserting due to starvation and

poor treatment from officers.

As we’ve seen, the military underfeeds and

underpays its troops, requires soldiers to pilfer food and supplies from

civilians, and suffers from bribery and favoritism at all levels. This

corruption leads to misery among the base of the pyramid and debilitation at

the top. From the regime’s perspective, this hurts both morale and fighting

capacity. One of the common misconceptions is that the corruption which

dominates the KPA is a deliberately designed system that directs power upwards

and speeds projects through the bureaucratic ether. But we’ve seen that the

KPA’s corruption is not a system at all, but rather the aggregate of

individuals motivated by necessity (and sometimes greed) to grab cash at the

expense of the army’s operational health.

This context provokes some difficult

questions. Would it even be possible to erode corruption without causing

irreparable damage to vital social institutions? Crackdowns would likely make

it even more difficult for North Koreans to eke out a living. Since everyone

and their uncle has a hand in the black/grey market, there is no criteria that

could possibly make a crackdown anything more than A). a scare tactic aimed at

arbitrary offenders or B). a political purge aimed at shoring up power.

Although it was an attempt to rein in on “renegade” merchants, the

2009 redenomination ultimately pushed North Koreans even further from the

regime’s grip than they were before. Aggressive, instantaneous measures that

threaten the livelihood of ordinary people are counterproductive.

In light of

this, the question is not: “How can North Korea crackdown on corrupt officials?” but

rather: “Will the regime ever be able to make bribery unnecessary?” They could

do so by increasing the salary of state employees like military officials,

which would admittedly be hard to do without going bankrupt. Furthermore, the

do-anything-to-survive, rugged individualism that now dominates the minds and

motivations of every North Korean is going to die hard and slow. The culture of

corruption is sustained by this mentality. Only years of stability and

increased faith in the government will change this. A push from the top brass

towards a modern military with an efficient chain of command – such as what we

saw in China – might also do a lot to begin changing the culture.

Given our understanding of corruption’s

place in the KPA, the next step is to assess what sort of measures, if any,

could be used to chip away at the problem. To find out, I will turn to China to

engage in a thought experiment. I’ll first analyze the seriousness of Xi

Jinping’s crackdown and then evaluate what sort of tactics could bear fruit in

North Korea. Stay tuned for the final segment.

*Views expressed in Guest Columns do not

necessarily reflect those of Daily NK.